The Urban Water Cycle

by Robert B. Sowby

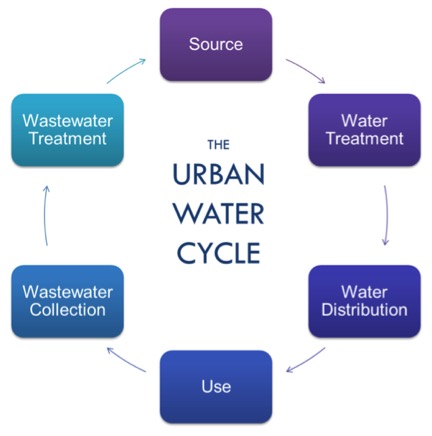

Most of us understand the basics of the hydrologic cycle—condensation, precipitation, transport ation, and evaporation. These processes operate on global scales and in natural environments. But on local scales and in engineered environments like cities, a different cycle dominates: the urban water cycle.

ation, and evaporation. These processes operate on global scales and in natural environments. But on local scales and in engineered environments like cities, a different cycle dominates: the urban water cycle.

For the first time in history, slightly more than half of Earth’s population resides in cities. (In the U.S., the number is already 80 percent.) The world continues to urbanize, with 70 percent projected by 2050. Providing safe, reliable water to urban populations will be a defining challenge of the 21st century.

Water, of course, is a part of everyday life, from supplying our drinking water to removing our wastes. It is also the largest mass flux into and out of cities—more than food, freight, people, or anything else. Just as water circulates in the global hydrologic cycle, water in our cities flows in an urban water cycle, one of the modern world’s fundamental systems.

Source

Many freshwater sources are found in the environment as a result of geological and meteorological phenomena. Surface waters such as lakes, reservoirs, and rivers are the most visible and are often tapped for public water supply. Groundwater, which exists almost everywhere at some depth, can be extracted by wells. The choice of a water source depends on many factors, including quality, availability, proximity, economics, and legal issues.

Water Treatment

To be suitable for distribution and human use, raw water must be treated to remove contaminants and pathogens. Design of appropriate treatment processes depends on water quality. At a basic level, disinfection is necessary to deactivate harmful microorganisms. More advanced treatment involves a sequence of screening, settling, filtering, disinfection, and chemical adjustments at a water treatment facility.

Water Distribution

After treatment, finished water is distributed to customers through a pressurized system of pipes, pumps, valves, and storage reservoirs. While much of this infrastructure is buried and invisible, it is an important system that ensures that water is available when and where we need it.

Use

Water customers use the supplied water for various purposes. Industries use water for manufacturing and cleaning. Businesses and offices use water for daily operations. At home, residents use water for cooking, bathing, laundry, drinking, and landscaping.

Wastewater Collection

The opposite of distribution, wastewater collection systems (sewers) collect used water and convey it, usually by gravity, to a wastewater treatment facility. This occurs through a network of increasingly large pipes. A typical urban wastewater stream is more than 99% water and less than 1% waste.

Wastewater Treatment

After use, water quality has been degraded and requires treatment before it can be reintroduced into the environment. Wastewater treatment uses physical, chemical, and biological processes to remove wastes from the influent and restore water quality. Once treated, the effluent is discharged to the environment and the cycle begins anew.

While these six components are typical, the urban water cycle varies among cities, or even among parts of cities. Sometimes an intermediate transmission step conveys raw water from a source to a treatment facility. In one shortcut, treated wastewater can be reused directly as reclaimed water; this can be practical when the effluent quality exceeds the natural source quality. Singapore, for example—highly populated but geographically small—is known for NEWater, its brand-name reclaimed wastewater.

While not directly included in the cycle, stormwater runoff can be transformed from a waste product into a resource by practices of low-impact development (LID). Rainwater harvesting is a shortcut from source to use, where rainwater is collected for outdoor applications such as gardening. A given urban system may combine all of these methods in varying degrees.

Each component in the urban water cycle brings its own benefits and challenges, and understanding them is the first step to developing sustainable water solutions for our growing population.

Population data: World Health Organization, http://www.who.int/gho/urban_health/situation_trends/urban_population_growth_text/en/

Robert B. Sowby is a hydrologist and consulting engineer in Salt Lake City and currently serves as editor of the Utah Water Blog.